Odd Art before the 1800s

Art Oddities and Stupidities from before the 1800s - the amusing, the mysterious, and the misunderstood.

Today, you can easily google examples of weird contemporary art. A simple search will show you categories like shock art on an array of media ranging from mattresses to urinals. It’s straightforward to find bizarre art today, compared to in the past.

Every country’s accessibility to art supplies and laws on what you can paint have varied in history. However, you could generally claim that most artists stuck to the style of their time. So if it wasn’t a Dadaist urinal they were making, it was a portrait of the Virgin Mary to please the Catholic church in the middle ages.

The various restrictions that artists faced in history meant that it was probably harder to spread art that diverged from the status quo. In our digital age, we’ve collected examples that did just that from the ancients to the 1800s.

Let’s start with one of the oddest: Belligerent bunnies in medieval manuscripts. Historian Jon Kaneko-James has explained that in the middle ages, rabbits were seen as a symbol of innocence, helplessness, and fertility. Most of these violent hares show up in books made for the clergy.

They were painstakingly challenging to make, involving a long process of turning animal skin into pages. Afterward, the makers would write the text by hand, extending the work-time to months or years. Naturally, this scarcity made medieval manuscripts expensive, which begs the question of why they included violent bunnies.

James’ description reveals that the makers had a sense of humor. Since people viewed rabbits as helpless and weak back then, medieval scribes thought it would be funny to draw them overpowering humans. Considering the popularity of the bunny attack scene on Monty Python’s Holy Grail, I believe that the scribes’ style of wit is still alive and well.

Apparently, it wasn’t only rabbits that liked to poke fun at West. Another example of bizarre art comes from the Edo period (1603-1867) of Japan; a set of scrolls called He-Gassen, which lovingly translates into fart battle.

The scroll stays true to its name, featuring a wide array of people tooting their enemies (which include cats, trees, horses, and each other) away. A 2012 article from the Daily Mail explains that there’s a deeper meaning to the madness. The Edo-period of Japan was partially characterized by its isolationist policies meant to separate it from a bickering Europe and its missionaries.

While the article says that these scrolls were a way to turn xenophobia into fun, that claim is somewhat questionable. Considering that the Japanese characters in the manuscript point their farts at trees, animals, and each other, it simply doesn’t look like the majority of it is meant to be particularly political or... serious.

What might be more likely, is that the artists were in it for a laugh. This scroll falls under the Ukiyo-E style, characterized by art on wooden blocks that were created for entertainment. They often featured flatulence as a part of a joke, so it’s no surprise others would follow suit. Where the art might have been hung or shared, though, is still a good question. The mixture of humor and curiosity makes this piece both mysterious and amusing.

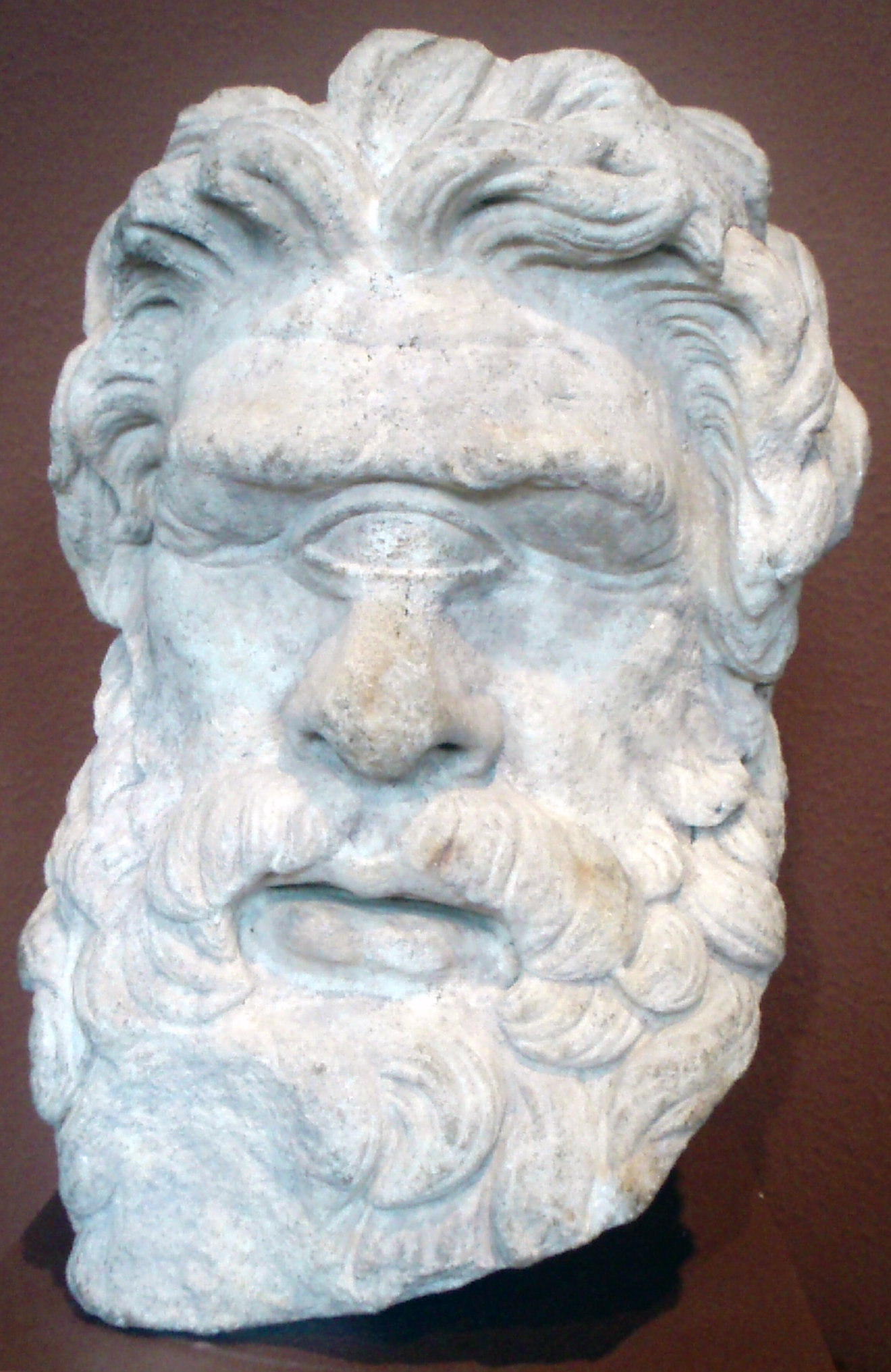

Another era known for its lively imagination comes from the Greeks and Romans. Although the following artwork has a legitimate myth that inspired it, it could be a surprising sight for many museum-goers in the Classical section: A cyclops.

According to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, this piece, the Head of Polyphemus, was created around 150 BC. This is based off a Greek myth featured in Homer’s “The Odyssey”. In the story, Odysseus and his men reach an island inhabited by violent, lawless cyclopes. They wander upon a cave that the giant Polyphemus lives within.

Upon seeing the humans, Polyphemus shuts the cave door, trapping the men in. Within the next day, Polyphemus eats four of Odysseus’ men. However, Odysseus understands that he can’t kill the cyclops yet because only he has the strength to open the passage to his freedom. Thankfully, the giant did open his door sometimes; namely to let his sheep go outside in the morning.

So the next night, Odysseus leads his men to stab Polyphemus’ only eye with a red-hot poker. Now that he was blind, he could only feel the backs of each sheep to ensure that the men weren’t escaping with them. But Odysseus and his men outsmarted the giant; they got away by tying themselves to the sheep’s bellies.

What makes Polyphemus an oddity is it’s one of the few Classical figures of a cyclops. In Ancient Greece, sculptors put great efforts into making statues look like the perfect form of a human body. The Romans, who sought to copy Greek masterpieces after, put their spin on the style by adding physical imperfections like scars and wrinkles. Both eras modeled their art after the human form, but cyclopes had no real examples (that we know of) to model after. This attempt at turning fictional anatomy into a bust makes the head of Polyphemus a unique treasure.

Unfortunately, not every ancient civilization left as many records as the Greeks. This means that for other society’s artwork, the inspiration behind their sculptures is more mysterious. One example of this is the eye idols from ancient Mesopotamia and Syria, 3300-3000 BC.

*Source: Wikipedia Commons

Their immediate appearances look almost alien-like, but these eye idols are thought to have potentially been an object of worship.

The Louvre’s Department of Near Eastern Antiques explains: In 1937-8, archaeologist Max Mallowan coined the term “eye idols” to describe the hundreds of figurines he found near a temple in the city of Tell Brak, Syria. Due to its golden, detailed décor, they called the building they were found in the “Temple of the Eyes”. The Met’s collection description indicates that large eyes were used to show attention to the gods in Mesopotamian art.

Another explanation says that the idols are representations of the ancient goddess Ishtar. She was associated with love and war, and deeply important to the Near East region. Aphrodite, Astarte, and many other goddesses followed her example, yet Ishtar is not well-remembered today. Since it’s more difficult to find records of early civilizations, it’s a shame that the eye idols may remain a mysterious artifact forever.

Until then, the best that we can do is to keep protecting ancient artwork. We might never learn what inspired a couple of artists to put together He-Gassen, or the stories of each person who carefully created an eye idol. Still, judging by the humor, faith, and creativity that brought this art together, maybe people from the past were not that different from us.

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use the website we assume Your acceptance on this. Read more